Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Reflections on Digital History

What I have learned is an easy, though lengthy answer, as it reads basically like the course syllabus. I have learned the power of the digital world and its potential use for historians, something already being explored by a number of academics and organizations. I have learned skills like HTML, CSS, blogging, tweeting, website design, data mining, visualization techniques, and how to create mashups and georeference with services like Google Maps. Furthermore, it has been impressed upon me that the internet is by no means a perfect medium, and that its democratizing aspect is both a great strength and a great weakness. Amateur history sites and reference sites like Wikipedia compete with academic history sites for peoples’ time and attention. I have learned that the best way in which to improve the internet as a source of good history is through engaging with it, be it through starting one’s own site, collaborating with others on theirs, or even just creating or editing Wikipedia entries.

Over the past few months, as I waded into this largely new world, I began to view things differently. The implications of copyright (and copyleft) have wide implications on my future work in public history, and while by no means an expert, I now have enough knowledge to comfortably navigate those potentially treacherous waters. I have also gained an appreciation of free and open source software such as CutePDF, and the graphic design programs GIMP and InkScape. I am also now more likely to notice the computers that subtly permeate our lives, and I try to think of ways in which these new (or new to me) technologies could be used in history or heritage.

Most importantly this course has helped to shape what kind of an historian I want to be. Prior to starting this program, my experiences had been in heritage, rather than history, and I believe this has come across in my blog posts. (A few weeks ago I ran my blog through the Blog Discourse Analyzer available through the Text Analysis Developers Alliance webpage and discovered that I had used the term ‘Heritage’ 36 times, where as the term ‘History’ only appeared 16 times.) I am passionate about local history and built heritage, and by taking this course I now have a better idea as to how I might better engage with the public and make history as relevant as possible through things like online publishing, interactive websites and collaborative online projects, as well as trough emerging technologies like augmented reality.

When I began this course, I was competent with both computers and the internet, but I never imagined the possibilities that have been presented to me over the past few months. I am looking forward to a second course with Bill, Interactive Exhibit Design, where I can continue engaging with digital technologies in a heritage-related context. This post by no means marks the end of this blog, and I plan to continue updating it as often as possible.

Thursday, November 26, 2009

Mapping Heritage Resources in Edmonton

This, among other things, led my classmate Catherine Caughell to create a map of her own, which she posted on her blog. She did such a great job that I really wanted to try it myself, hence this post.

I used the Inventory and Register of Historic Resources in Edmonton as a data set, which is available on the City of Edmonton's website. This document includes the City's register of designated resources, the resources that have been recognized on the inventory, and resources that have been demolished.

Using this data set I spent a few minutes with Google Maps and Batchgeocode.com to map out the locations of the City's designated heritage resources.

View City of Edmonton Designated Heritage Resources in a larger map

The above results represent only an hour or so of work, and now that I know the basics, maps I create in the future should take even less time.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

Numeric vs. Values-Based Evaluation of Heritage Properties

This is an extreme illustration of only one of the problems associated with a numerically-based evaluation system for heritage resources. Let me first say that when London revised their system, they used several other municipalities’ systems as guides, so they are by no means alone in dealing with the potential problems caused by a numerically based system.

A common critique of the numerically-based system is that it only values what is “old and beautiful”.[ii] Other shortfalls of a numerically-based system include the following.

1. Architecture, particularly high-style architecture, becomes over-represented due to the inflated scores it receives.

2. Representative examples of vernacular and working-class structures remain under-represented because they receive too few marks in the Architectural Significance category (which in London’s case is 42% of the marks, 50% if you include Landmark, which is often the case with high-style residential architecture).

3. The emphasis on architecture makes the designation of cultural landscapes more difficult.

4. The use of a formula in determining significance (or degree of significance) obfuscates the fact that evaluation is a very subjective practice. Individuals will undoubtedly interpret terms differently if they are not defined, such as determining rank based on associations that are “very strong”, “strong” or “moderate”. Until somebody defines these terms and makes the definitions widely available, there is no way to ensure consistency in evaluations.

A possible solution to the issues raised in numerically-based evaluation systems is the increasingly common practice of values-centred significance. In this system, a resources is considered to be either significant or not. It can be significant for any number of reasons, all of which are included in the London evaluation system. The difference is that in the values-based significance model a resource merits designation if it fulfills even a single criterion (although most fulfill several).

Benefits of values-centred evaluation include the following.

1. It is easier to designate buildings that are not of high architectural significance.

2. It accepts and legitimizes a whole range of values apart from the “old and beautiful”. This also recognized that values can change over time, and that different people can value the same resource for different reasons.

3. It lends itself to the designation of cultural landscapes which may not have architectural features to evaluate.

4. While still subjective, it makes the process far more transparent because interested parties will know exactly why a resource was designated rather than have to explain the scores given by multiple committee members and the reasoning behind them.

5. Values-based evaluation “can yield much more detailed, sensitive appraisals of significance” because they are not tied down to pre-determined questions about what is significant.[iii]

Values-centered evaluation is widely practiced, and has been gaining increasing popularity for a number of years. The federal government, as well as most, if not all provincial governments subscribe to this system, as do many municipalities. Perhaps it is time the City of London did as well.

[i] London Cultural Heritage Resources: Building and Property Evaluation Sheets, 10.

[ii] Randal Mason, “Theoretical and Practical Arguments for Values-Centered Preservation” CRM; The Journal of Heritage Stewardship Vol.3, No.2 (Summer 2006), 35.

[iii] Randall Mason, “Fixing Historic Preservation: A Constructive Critique of ‘Significance’” Places, Vol.16, No.1, 2003, 68.

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Digitized Books Online

This week in my digital history class, my professor, Bill Turkel, charged us with a very interesting task. He asked that we select eight books as found in the 1913-1914 Eaton’s Catalogue and find full digitized copies of them online. The following is explanation of the books I selected and my results.

Going through the hundreds of books listed in the catalogue, I tried to select a wide range of titles and genres, and attempted to pick obscure titles, although to be honest, I know so little about turn-of-the-century literature, that most of the titles were totally lost on me.

One of the first books I chose was Gospel Hymns Nos. 1-6, a hymnal that I have seen in the archives of my church, and I was therefore naturally curious as to whether or not it had been digitized and made available online. I was not disappointed, and quickly found the resource on the Internet Archive. It was part of the Americana Collection, and had been digitized by the Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries in Illinois. Formats available include a page view digitization available for view or download in a PDF format as well as a text only version in HTML markup, though I am not certain if the text had undergone additional SGML markup. It was interesting to see the work in text only, with no sheet music, because it provided a very good example of how a textual representation of a work can result in the loss of meaning.

Another book I chose to search for was Radford’s Practical Barn Plans. My experiences documenting farm buildings in Alberta have led me to realize how little information is available on barns and outbuildings in the province, and I am therefore always interested in broadening the scope of my knowledge. Again, I was not disappointed by the Internet Archive, through which one can search Google Books, the project under which this book had been digitized in 2007. Again, both page view and HTML were available, and it was another example of how meaning can be lost, as anyone trying to build a Radford-designed barn would struggle with the lack of graphics provided in the text only HTML version.

I also searched for several novels, including The Land of Oz by L. Frank Baum, a sequel to The Wizard of Oz; With Wolfe in Canada by C.A. Henty; A Very Naughty Girl by Mrs. L.T. Meade, advertised as a “Well-known and immensely popular novel”; and the boys’ adventure novel The Boy Scouts in the Philippines, which turned out to be a fascinating look into American imperialism at the beginning of the 20th century. I was able to find all of the above titles with little trouble. The Land of Oz was included in the Americana Collection, With Wolfe in Canada was digitized by the Gutenberg Project, and the Boy Scouts in the Philippines had been digitized by Google, and all were accessible through the Internet Archive. L.T. Meade had a number of books available through the Internet Archive, but A Very Naughty Girl was not among them. I ended up locating it through both Google Books, and the Electronic Text Center of the University of Virginia. Meade’s book was presented in text only, though with proper formatting, page breaks and page numbers. This seems to me a very suitable medium for the digitized copy, as the textual content is of primary significance, and the loss of information seemed negligible.

The final two books in my search proved surprising. Neither The Mystic Dream Book (because dream interpretation from the 1910s sounded really cool) nor The Galt Cook Book (because I love to cook) were available through the Internet Archive, but I did discover that they are both currently in print. The Mystic Dream Book is listed through Google Books, leading me to believe it has been digitized, however it has been republished 1937, 1992 and 1998, and new copies are currently available through Amazon, which is likely which Google has not made the text available. The Galt Cook Book was re-released in 2001 as The Early Canadian Galt Cook Book. When I discovered this, I thought it was a lost cause, but I tried a quick Google search and discovered it has been digitized and made available through Library and Archives Canada, as part of their online exhibit Bon Appetite: A Celebration of Canadian Cookbooks.

Through the process of these searches, I came to the following conclusions:

- The staggering number of digitized texts available through the Internet Archive, Google Books and other similar initiatives are an excellent source of information.

- Aggregator sites such as the Internet Archives are great tools, but are not perfect. Searching within individual project databases may provide titles the Internet Archive missed. Also, Google’s algorithmic search is a very powerful tool for finding digitized material.

- This process has reinvigorated my interest in copyright and its inherent limitations on the reader. If we could deal with the copyright issues on out-of-print books, particularly those for which the copyright holder can no longer be found, the possibilities for Google Books, the Gutenberg Project and the Internet Archive, among others, is astounding.

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

My new webstie, or, my shortest postever

I created it through Google Sites (a very easy process) although my rudimentary skills with HTML came in handy in a few instances. Feel free to take a look - any feedback is much appreciated, as I plan to continue refining and expanding the site as time permits.

Saturday, November 7, 2009

GIS and Public History

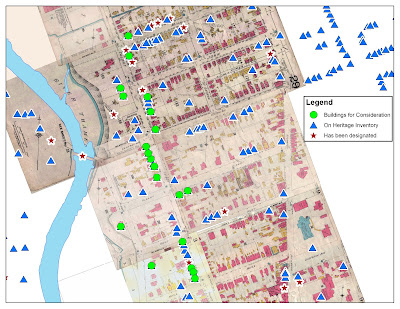

I recently received an introduction to GIS from Don Lafreniere, a graduate student in the Geography Department of UWO. Don showed some of my fellow students and me the things they were doing with GIS as historical geographers, much of which related directly to public history. For example, my classmates and I are currently researching homes in London neighbourhood to determine whether they qualify as historic resources. One criteria of significance in Ontario is contextual value, where the property is important in defining, maintaining or supporting the character of an area, or is physically, functionally, visually, or historically linked to its surroundings. (Designating Heritage Properties, Ontario Heritage Toolkit). We asked Don to create a map including all of our buildings, all the buildings in the area that are already designated, and all the buildings in the area that were included on the most recent heritage inventory (meaning they have been identified as significant but not yet designated). The resulting map took him only a few minutes to make, but should prove very useful when we argue for the contextual worth of our buildings to the local heritage review board.

GIS is certainly not new technology to heritage planners, but volunteer heritage boards have likely not had as much experience with the possibilities presented by GIS. Having someone at the meetings manipulating maps in real-time would make their decisions of what to designate, particularly when it comes to heritage areas, much easier. Saving the sequence of maps they created and viewed would also help them explain their reasoning latter, and would help establish more concrete precedents for them to look back on in the future.

One project the UWO geographers are working on is using GIS to map historic photographs, which would be an amazing resource for archives and those researching in them. The basic idea is to scan historic photos, tag them using Picasa(free software from Google) and then plot them with GIS so they will appear as points on a map. This project employs two of the most commonly used archival resources, maps and photos, and will help archives make these materials more accessible both physically and intellectually.

Because many of the users of an online geographically referenced historic photo collection would be non-academic, it is worth discussing how we can get the public to engage in the project. One way in which this could be done is through folksonomies (see The Hive Mind: Folksonomies and User-Based Tagging). Many archival collections have hundreds of thousands, if not millions of photographs, and the volume is far too large for archives, which struggle for funding as it is, to do it themselves. Having denizens of the internet tag the photos with geographic locators and keywords is a reasonable solution. One of the major criticisms of such an approach is that there is no unified language used in the description. For this reason, I would advocate creating an extensive list of keywords from which the user would have to choose, based on a codified list of terminology commonly accepted by archives, such as the UNESCO Thesaurus. An “other” category could exist which would allow the user to create their own tag, but it could not be the only identifier used. The “other” field would allow users to create their own meaning out of photos while giving project administrators an idea as to any popular tags they may have missed. Controlling the tags would also eliminate spelling errors, and allow for both keyword searches and Faceted Navigation.

Unfortunately, GIS is proprietary software and is currently too expensive for many non-profit institutions. However, the potential is there for an extremely useful, interactive tool that would help promote and engage the public with their past.

Monday, October 26, 2009

A Quick Introduction to Intangible Cultural Heritage in Alberta

So, what exactly is ICH? The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (better known as UNESCO) is a good place to start, as they have been actively involved in the conservation of ICH for a number of years. In 2003 the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage was adopted at the UNESCO General Conference in Paris. The Convention defines ICH in the following way:

“The “intangible cultural heritage” means the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage.” (Article 2.1)

In March of 2009 I attended a workshop on ICH presented by the City of Edmonton and conducted by Dale Jarvis, intangible cultural heritage development officer for the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Over the course of the workshop, Dale explained to participants that ICH is manifest in many ways, but can be broken down into the following five categories:

The examples I am going to use came out of this workshop, and represent types of ICH found in a range of cultural and religious communities throughout Alberta. As you read you will no doubt notice some examples that fit your community as well.

Oral traditions and expressions encompass a number of different things, most notably languages. UNESCO has developed a list of the world’s endangered languages, four of which are located in Alberta. Other oral traditions and expressions identified by workshop participants included place names, particularly those which were informal or colloquial; immigration stories; camp songs; hymns; joke; playground games; and saying and rhymes such as those contained in the 1913 Western Canadian Dictionary and Phrase Book.

Performing arts identified as ICH in Alberta included the Shumka Dancers, a representation of Edmonton’s large Ukrainian population, as well as the emerging ICH of Aboriginal hip hop. Non-traditional instruments such as the spoons or whistling were also mentioned by several participants.

Social practices, rituals, and festive events included community fairs, exhibitions, rodeos, farmers markets, tea dances, perogy suppers, sports days, camp revival meetings, corn mazes and the Chautauqua.

Beliefs were a very interesting subset of ICH, and included such things as the use of horseshoes for luck, sayings about the weather, children not stepping on cracks, and Ukrainian practices of never shaking hands over the threshold of a home, leaving an axe in the doorway of the barn on New Year’s Eve to keep out evil spirits, and not whistling at the dinner table (young ladies who whistle at the table are said to marry bald men).

Skills and knowledge identified as ICH in Alberta include the construction of thatch roofs (a traditional Ukrainian building technique), local gardening techniques and knowledge of native vegetation, knitting, cooking traditional recipes, midwifery, and home economy skills such as making homemade cleaning products.

What are some examples of ICH present in your community, and how is it being preserved? It can be as simple as pulling out one of your grandmother’s recipes, or as complicated as mastering Ukrainian dance. Whatever it is, I will echo Dale Jarvis’ closing remarks at the workshop, and urge you to go out and get involved with ICH in your community; to make a conscious effort to preserve the intangible cultural heritage that is relevant to you.

If you are interested some of the things Canadians are doing to preserve their intangible cultural heritage, feel free to browse the links below.

Tags

AlbertaIntangible cultural heritage

Intangible heritage

Heritage in Alberta

Intangible heritage in Alberta

Intangible cultural heritage in Alberta

UNESCO

Sunday, October 18, 2009

The Leather Archives and Museum

While scholarship is present at the institution, the material is not presented as a one-way dialogue between expert and novice. Rather, the public is invited to engage with the Leather Archives and Museum by recommending library material to add to the collection.

The Leather Archives and Museum is active in the local community, and has had an average of 53 meetings or events per year since opening their doors in 1999. This is pretty impressive for a museum that is only open 4 days a week. The museum is also active in the online community, and maintains profiles on LiveJournal, Going, MySpace, YouTube, LibraryThing, Flickr, Facebook and Twitter.

Another interesting thing about the Leather Archives and Museum is its use of the internet. Because it is a small specialty museum it does not get an abundance of visitors to the site (the yearly average according to the website is only 1,133). However, the website gets over 400 unique hits a day, and over half of the visitors bookmark the site (also according to the website).

I could go on and on, but I told you this one would be short (I lied). I will end by urging you to check out their website, and especially their newsletters (they’re under Resources). The Leather Archives and Museum is a great example of a number of things:

1) how the gap between scholarship and public consumption is being bridged;

2) how “amateurs” can be the “experts”, harkening back to the days before the professionalization of history;

3) how a dedicated group of people can create a truly unique educational opportunity;

4) how the power of the digital age can be harnessed to develop your cultural institution as a physical and online community;

5) and how someone interested in oral history can unexpectedly gain a new appreciation for leather.

Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

This past Friday I was lucky enough to take part in the UWO History Society`s 25th annual field trip, which took me to two sites, the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum and Dundurn Castle, both located in Hamilton. Although Dundurn Castle was disappointing, I was really impressed with the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. Located near the Hamilton Airport, what makes this museum special is that many of their aircraft are kept in flying condition and are flown on a regular basis. At the beginning of our tour, long-time museum volunteer Ted Lowrey asked us to contemplate during our visit whether we felt it appropriate for the museum to fly their artifacts, particularly as some are quite rare. In this blog post I want to introduce some of the issues inherent in his question and provide readers with hopefully enough information to make an informed decision for themselves.

Preservation

The Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum has been criticized for flying their aircraft partly because it puts the artifacts under undue strain and risk. This is a valid concern, as every few years tragedies occur at air shows when vintage planes crash and their pilots are killed. On the other hand, flying aircraft ensures their preservation. Because of the dangers associated with flight the Museum`s planes must be kept in excellent repair through preventative conservation to ensure the pilot`s safety. Therefore, what better way to ensure their proper care than by flying them regularly.

Authenticity

To help ensure the safety of everyone involved in the flights, some planes have had their original engines replaced with different models. In many cases this increases not only the safety of the aircraft, but its value as well. However, does replacing the original mechanical components of the plane negatively affect its authenticity? Sometimes. It was common practice during the active service of a number of planes to replace their engines to make them more effective. One well-known example of this was the Mustang, which became a well-respected aircraft during WWII when its original engines were systematically replaced with higher performance models. Therefore, if the engines are changed to period appropriate models then I do not believe the integrity has been compromised. However, other practices are more suspect. For example, some vintage plane aficionados have been known to install autopilot systems in their vintage planes, a slight against authenticity not only in the eyes of many museum professionals, but among many vintage plane enthusiasts as well.

Cost

Museums are not generally known for their overflowing coffers, and the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum is no different. The vast majority of mechanical work is done by museum volunteers (there are 300 of them), yet still, 75% of the museum’s $5 million annual operating budget goes towards the preservation and restoration of planes, as well as the fuel required to fly them. One of the ways in which the museum raises funds is by selling rides to members on select aircraft , which run from $50 for a 20 minute ride in a Dakota DC3, to $2000 for a 60 minute ride in a WWII Avro Lancaster bomber (one of only two left in the world capable of flight). While the prices might seem steep (or not, depending on how much you like planes), fuel is expensive, and increased flights mean increased strain on the planes, which in turn requires more frequent maintenance, which for something like the Lancaster can cost over $100,000. With these associated costs, is continuing to fly the collection financially sustainable?

In flying their aircraft, the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum raises a number of issues, such as preservation, authenticity, and associated cost, but in doing so they differentiate themselves from other museums with similar collections. They also have the opportunity to use their planes as travelling exhibits, which was done in the summer of 2009 when the Lancaster was flown from Hamilton to Edmonton, stopping in various locations along the way, typically met by large and excited crowds. This gave a large number of people the opportunity to see an important part of Canadian history which they otherwise may never had had a chance to experience. Should the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum fly their planes? I would argue yes, they should, but I put it to you to decide.

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Copyright is giving me a headache

I would like to end with two related quotes, the first by Thomas Jefferson (taken from Paul Courant’s “Scholarship and Academic Libraries (and their kin) in the World of Google”), and the second from Banksy, a graffiti artist and author of the ironically copyrighted book Wall and Piece.

“If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of everyone, the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it.”

Thomas Jefferson (1813)

“Any advertisement in public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours. It belongs to you. It’s your to take, re-arrange and re-use. Asking for permission is like asking to keep a rock someone just threw at your head.”

Banksy (2006)

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Strategies in a Culture of Digital Abundance

Understanding the abundance of sources is essential if historians are to assist in their preservation and future use. Born-digital and digitized versions of analogue materials are being created at an astronomical rate. According to Lyman and Varian's "How Much Information", in 2002 alone five exabytes of digital information was produced – the equivalent of the contents of the Library of Congress, multiplied 37,000 times.

A number of different groups are working towards the preservation of this overwhelming amount of information, including archivists, librarians, private individuals, governments and corporations, although historians have thus far not been well represented. Preservation attempts have included creating direct print analogues or migration to more easily preserved mediums, however these projects lose the inherent value of the digital medium such as links, hypertextuality and the interactive or experiential aspect. Others have salvaged original equipment to ensure future readability of their documents, but these machines have a limited lifespan. The technical solution of emulation software has also been suggested but currently it is only a theoretical solution. While some believe that a perfect solution of total preservation is possible, it is unlikely that such a solution will be discovered in time to save much of our current digital culture, which is constantly disappearing. Rather, a combination of all of the above must be used to create effective, practical solutions to the preservation of digital culture.

As a result of the rapid growth of digital resources, the issue of ownership must be rethought. Already the source of debate by archivists and librarians, historians must enter the discussion. Private individuals and companies such as The Internet Archive, Microsoft’s Corbis , and several large publishing companies such as the Thompson Company have taken an entrepreneurial approach to digitizing analogue material and preserving/creating born-digital material. While the results of some these projects are freely accessible (as is the case with the Internet Archive through its Wayback Machine, most of the resources are leased to users for a profit. The corporations that control digital versions of analogue material, even those in the public realm, effectively own them as they control their access and use. In turn this has created what some call the “second digital divide”, disenfranchising scholars without access to universities that can afford the licensing fees, as well as high school students and teachers, the general public, and economically underdeveloped organizations in North America and abroad.[1] Ownership by corporations also affects the will and legal ability of libraries and archives from preserving the material. This is worrying, as libraries and archives have traditionally been responsible for the preservation of the historical record, and the corporations, who see digital content as a means of revenue generation, have no long-term preservation plans for the materials and may cease their operations once it is no longer profitable, with potentially devastating results to the contemporary historical record

The idea of authority, traditionally seen as the prerogative of academics, must also be rethought as a result of the current digital age. The widespread availability of sources online is creating greater accessibility of scholarly work to the public (even though much of it is hidden in the deep-web), and is making the work of amateurs and enthusiasts much more prevalent, which serves to erode traditional scholarly authority. Another example of the erosion of traditional authority is Wikipedia, which encourages contributions from everyone. Not only does this new forum not defer to academics, but it enables members of the public to directly challenge academic authority.[2] Authority of documents themselves is also becoming a greater issue. While analogue materials have long been subject to forgery, the ease with which a digital document can be faked is far higher, and it will no doubt take some creative thinking to ensure the continued authority of the historical record, as well as building public and scholars’ trust in the new digital medium. The authority to preserve digital material must also be evaluated. As mentioned above, due to restrictions on use by the companies who control access to the material, the traditional keepers of our shared memory (libraries and archives) can no longer preserve material in their traditional manner. Government departments are typically understaffed and underfunded, and cannot be looked to as standard-bearers. Even the private companies such as the Internet Archives, which uses bots to crawl the web taking snapshots of web pages, are limited in their preservation attempts by the aforementioned gated access and copyright restrictions.

In order to begin actively preserving today’s digital culture cooperation is needed between historians, librarians and archivists; between academics and the private sector; and between academics and non-academics. Many historians have taken the view that preservation is the responsibility of libraries and archives, and have therefore stayed out of the digital preservation dialogue. However, historians will be directly affected by the outcome of current strategizing, and therefore have a responsibility to engage in the debate. Although historians would like to keep everything, whereas librarians and archivists must take a more practical approach based on available resources, the three parties have a common purpose – to ensure the preservation of at least some of our current digital culture. As a united front, historians, librarians and archivists should cooperate with the private sector, which has the potential to be an able collaborative partner through funding, technology, and access to the vast digital collections already assembled. Finally, academics must be ready and willing to cooperate with the non-academic public, because ultimately, the current digital historical record should be preserved not just for academics, but for everyone.

[1] Rosenzweig, " The Road to Xanadu: Public and Private Pathways on the History Web," Journal of American History 88, no. 2 (Sep 2001): 548-579. http://chnm.gmu.edu/essays-on-history-new-media/essays/?essayid=9; Rosenzweig, " Should Historical Scholarship Be Free?" AHA Perspectives (Apr 2005). http://chnm.gmu.edu/essays-on-history-new-media/essays/?essayid=2

[2] Rosenzweig, " Can History be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past," Journal of American History 93, no. 1 (Jun 2006): 117-146.

Saturday, October 3, 2009

Struggling to Define Public History

I have recently read several articles attempting to define public history and its relationship to academic history and was relieved to discover I was not the only one struggling to establish a succinct and easily explainable definition of public history. Of the numerous definitions and explanations I came across, I would like to share those which, to me, seemed the most intellectually approachable.

Margaret Conrad, in her article “Public History and its Discontents or History in the Age of Wikipedia” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 18,1 (2007): 1-26 defines public history as “applied heritage” and the “adaptation and application of the historian’s skills and outlook for the benefit of the public and private enterprises.” She also quotes from Debra DeRuyver, main editor for the Public History Resource Center, who lists the following as main elements of public history:

· “theories, methods, assumptions, and practices guiding identification, presentation, interpretation, and presentation of historical artifacts, texts, structures and landscapes in conjunction with and for the public;

· the interpretive process between the historian, the public and the object; and

· the belief that history and historical-cultural memory matter in day-to-day life.”

Rebecca Conrad in her article “Facepaint History in the Season of Introspection” (The Public Historian 25,4 (2003): 9-24) also mentions public historians’ acceptance, or even their embrace, of shared authority in interpretation. She goes on the explain that public historians do more than simply disseminate the knowledge of academic historians to the public, and that public historians do not work solely in museums, archives and historical sites. She contends that public historians distinguish themselves from academic historians not by where they practice history, but by how they practice it. Citing Donald Schön’s idea of “reflective practice”, Rebecca Conrad states that public history is practiced first through a foundation of historical knowledge and past experience. Using this foundation, public historians identify the problem (whatever it may be) and design an appropriate intervention, creating a scholarly defensible answer to a real world problem.

Based loosely on my own experiences, an example of this might be the case of a rural fire department (not to disparage rural fire departments) who want to burn down an old schoolhouse to allow them to practice fire-fighting, but the local historical association is up in arms about the potential loss, and a county meeting is held to debate the issue. A public historian is invited to mediate between the two sides, and to develop an answer to what to do with the building. Like an academic historian, the first job of the public historian would be to steep themselves in the history of the area and the particular site. This would also be an opportune time to speak with the community and discover why they value the site – its history and significance from the public’s perspective. From this base knowledge, the public historian could explain what would be lost should the building be destroyed, and, based on their prior experiences with similar projects, what might be gained should the building be saved and rehabilitated.

After my first, albeit brief, foray into the world of public history, were I asked again by the review board, just what is public history, I would have a vastly different response, and while I know it would not be perfect, it might go something like this:

“In many ways public history is similar to academic history, in that both disciplines research, write and publish on historical topics. However, public history is different because it includes working with the public with non-traditional resources such as material culture and oral history, to identify, interpret and present their past in a way that is both meaningful to them and academically defensible.”

Sunday, September 27, 2009

SenseCam

Now when I first head about this technology, I was unimpressed. With such an enormous amount of digital information being created every year, how are we going to deal with large amounts of people documenting their entire lives? Just to put this "enormous amount" of information into perspective, in 2002 five exabytes of digital information was produced. To put this into context, this amount of storage space is enough to store all the information in the library of congress, which contains 17 million books, 37,000 times over. If you're interested in these numbers check out Lyman and Varian's "How Much Information".

My opinion of Microsoft's SenseCam was change today, while I was walking through an old neighbourhood looking at the home (one of my favorite pastimes). It struck me how much more I could get out of my hobby of exploring residential architecture if I could easily record everything I saw. It would enable me not only to permanently archive my travels, but I could easily compare and contrast different neighbourhoods within a city, a region, a province, the country, or internationally. This technology would make decisions about heritage conservation and planning easier because you could take conservation boards on virtual tours of the area so they get a better sense of what they are dealing with. You could even perhaps tag buildings as you look at them based on architectural details, materials, style, design, significance and integrity, to name but a few. What's more, the cameras can record GPS information about where the photos were taken, making it easy to trace where the buildings are located.

Although SenseCam is only a research project at the moment, I can't wait for them to become commercially available so I can get one.

Saturday, September 26, 2009

Katyn

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0879843/

Monday, September 21, 2009

Why Teach History

Seixas’ articulation of why we should teach history was very enlightening. Being a student of history, I of course have long-know its study is important, but it was more of an innate sense of value rather than an easily digestible list, such as Seixas has provided.

He outlines a number of benefits to teaching history (and thus developing an historical consciousness), including that:

- history helps to shed light on present realities;

- history helps shape our sense of identity;

- judging past actions can explain indebtedness of some groups to others based on past injustices;

- history can serve as a benchmark for determining if our present realities are getting better or worse;

- and an historical consciousness can help us to think critically about what stories about the past we should believe, and what stories about the past we should tell.

I would urge history-lovers to keep this list handy (as I plan to do), for the next time someone scoffs at the study of our past as an irrelevant.

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Social Media Revolution

The following is a video created by Eric Qualman. His blog, Socialnomics - Social Media Blog, along with more information about the video can be found at http://socialnomics.net/2009/08/11/statistics-show-social-media-is-bigger-than-you-think/

The rapid, wide-spread dissemination of social media technology as described in the above video is precisely why historians, educators, museums workers and archivists must embrace technological advances and work towards new ways of engaging with the public. If the discipline of history cannot stay abreast of technology it may prove difficult to maintain relevance to mainstream society. At present there are many people actively working on history in the digital realm, evidenced by the numerous history-related blogs being written. An excellent list of some of these blogs can be found at Cliopatria’s extensive History Blog Roll (http://hnn.us/blogs/entries/9665.html). History blogs are an excellent example of how the study of history can use digital technology to reach vast numbers of people. The adoption of this type of technology will no doubt have effects on both the practice and perception of history, and though many are reluctant to embrace the Social Media Revolution we must accept these changing realities or possibly be left behind.

"Science and technology multiply around us. To an increasing extent they dictate the languages in which we speak and think. Either we use those languages, or we remain mute.” J. G. Ballard

Monday, September 14, 2009

Public history is everywhere (even in cows)

The final article I saw relating to public history is "Calf birth is 'cool'". Bear with me! This article is about this past weekend's Western Fair, at which over 100 people witnessed the birth of a calf. Now a few days ago I would have just said neat, but it has nothing to do with public history. However, today I was reading Museums in Motion by Edward Alexander, in which he describes zoos and botanical gardens as museums in which the objects are living things. Furthermore, Elain Heumann Gurian, in her article "What is the Object of this Exercise?", states that a museum object could also be an experience. Following the logic of these two scholars, I would argue that the birth of a calf at the an agricultural exhibition falls under public history. Who knew.

Hello good people of the internet!

I have always loved history and museums, and some of my best memories growing up revolve around trips to Calgary's Glenbow Museum and the city's large living history museum Heritage Park.

I have been working and volunteering in museums and archives for the past several years, including stints at the Lougheed House, a national historic site in Calgary, where I acted as a costumed interpreter and spent a summer in the archives; the Lock 3 Museum in St. Catharine's where I assisted in the collections department cataloguing textiles; and for the past three years at Heritage Collaborative Inc., an Edmonton-based consulting firm specializing in heritage planning.

I am really excited to begin my studies in public history at Western. It is going to be a big change from Edmonton, where I left my beautiful wife and terribly-behaved (but really cute) dog Mika, but I am ready for the challenge.